Sometime in the early 90s, my maternal grandmother was terminally diagnosed with colorectal cancer. She would undergo renowned Ayurvedic and First Nations herbalism treatments in addition to a mindful exercise regimen, which would mark her passing almost a decade later [as opposed to the mere months doctors expected]. Of course, I was too young to understand this prognosis. All I could fathom was the anguish of bereavement upon her loss. This was corroborated by several accounts of others who continue to affirm that I was never really the same after that loss—which would be punctuated by the relocation of my father, provinces away from me, shortly thereafter.

Back then, I think, was when I started to second-guess the value of my emotions. What was the point of so much, if any sadness? Moreover, these early losses inform the way I view impermanence. These voids—especially since I couldn’t understand them, even though I felt their weight—naturally inclined me to undermine feelings. Specifically, investing in feelings that only lead to pain. This would also mark when, how, and why I felt an aversion to change because these transitions left me unmoored. These days, I find myself impassive as I sit with my grief rather than run from it. Happiness, I’ve accepted, isn’t found by trying to alter the past or secure a perfect future; it comes from being present. Love and loss are intertwined. Neither the acquisition nor pursuit of happiness concerns chasing time but accepting its passage, embracing moments that are ours to cherish.

This is something I remind myself after the terminal prognosis of my cat, Edith, my maternal grandmother’s namesake. Over time, I realized that oversight defined a lot of how I bereave the departed. I agonize over not being able to see or care for Edith again. I want to protect and comfort her, even beyond this life. It’s a love that transcends time, and I recognize this bond isn’t easily broken by life or death. I like to think that my love for her will always be a part of her journey, here and beyond. However, I can’t help but feel sadder as I grow more self-aware and attuned to the impermanence around me. I’m sure my neurodivergence (amongst a plethora of adversities) factored into how hopeless I’ve felt and the [very rational] conclusion that engaging with the world emotively can only lead to further loss. But no one can refute the impermanence of life.

Maybe that’s why, try as I might, I can’t shake my fascination with The Flash (2023).

Unlike the DC Universe Animated Original, Justice League: The Flashpoint Paradox (2013), a curious live-action interpretation marked the latest foray by the DC Extended Universe in The Flash (2023). Both films are adaptations of Flashpoint, a 2011 DC Comics crossover wherein Barry Allen (Ezra Miller) travels back in time to prevent the murder of his mother, Nora (Maribel Verdú), which inadvertently creates an alternate reality on the brink of apocalypse. But The Flash sees Barry sent further back in time where he’s knocked into an alternate timeline by another time-traveller. Therein, he encounters—and coexists with—a younger, happier version of himself (also played by Miller) prior to the trauma that would’ve come to affect most of his life. This duality adds a layer of introspection as Barry not only confronts the consequences of his time-altering actions, but also the person he could’ve been had iniquity not defined him. Yet, his time travel creates an alternate reality where superheroes are missing or changed, and Earth is threatened by General Zod’s (Michael Shannon, reprising his role from Man of Steel) invasion. He teams up with his younger self and the timeline’s Batman (Michael Keaton) and Supergirl (Sasha Calle) in an attempt to save the timeline by defeating Zod.

Central to the narrative is retrocausality, the concept that future events can influence the past, as Barry realizes his intervention causes disastrous changes to the timeline which affect both past and present realities. Another key narrative element here is fate, the idea that certain events are predetermined and unavoidable, when Barry recognizes that death—the deaths of his family, friends, and other allies—mark fixed points in time that can’t be changed. Thus, all is for naught as the heroes face Zod and his fellow Kryptonians. The Barrys find themselves woefully outmatched. Their attempts to engineer a favourable outcome are futile because despite any of their interventions, Batman and Supergirl invariably perish. The end of this world is assured as Zod deploys his World Engine to terraform Earth and repurpose the planet as a new Krypton.

Eventually, Barry faces the Dark Flash (also played by Miller)—an older, battle-scarred version of his alternate self; uniquely conceived for this film—who has been obsessively trying to “fix” this doomed timeline, running through time for an eternity as he attempts to engineer an outcome where everyone lives. He admits to pushing Barry into this timeline to ensure his own existence wherein he [Barry’s alternate self] could acquire his powers. This relates to earlier in the film when Barry reveals to his longtime crush—Iris West (Kiersey Clemons)—that his resolve to work in forensics was driven by a desire to correct systemic failures which belabour judicial and evidentiary oversights, as he also seeks to exonerate his father—Henry (Ron Livingston)—who was wrongfully convicted of Nora’s murder. Since Nora never dies in this reality, alternate Barry lacks the driving force to be a forensic chemist—and so, never interns at the forensics lab wherein he would’ve been struck by lightning and doused in chemicals to gain his powers. This necessitates the Dark Flash knocking original Barry into this timeline whereupon he, in an effort to preserve his future and ensure he can go home [to his own timeline], guides his alternate self to orchestrate this accident. The Dark Flash muses about how close he is to “fixing” everything, having run back in time over and over again to orchestrate an outcome in which Nora, Batman, and Supergirl are alive.

But his efforts wreak havoc across the multiverse.

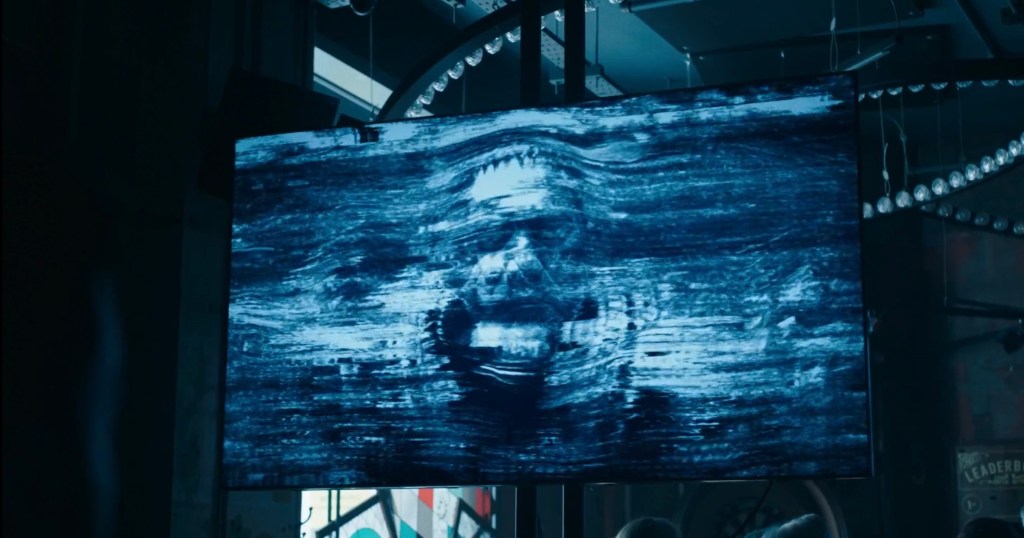

We see glimpses of alternate worlds and peoples. There’s one where Christopher Reeve and Helen Starr observe as Superman and Supergirl; another where George Reeve is a Superman who oversees Jay Garrick; and one where Adam West’s Batman chases a Joker played by Cesar Romero, among others. All of them degrade as the Dark Flash’s interventions compromise the cosmic order. His interference doesn’t just destabilize the multiverse. It degrades time itself. His obsessive attempts to alter events also render his very own reality unsustainable. On principle, the implosion of other worlds won’t spare this one. Still, the Dark Flash insists that he can “fix” things, then moves to kill Barry lest he jeopardize this objective—but is undone when he mortally wounds the alternate Barry who dives between them. Accepting this tragic outcome, Barry departs to undo his initial alteration, understanding that restoring the original timeline is the only way to prevent further chaos and preserve cosmic order.

In contrast to The Flashpoint Paradox which emphasizes alterity and irrevocable outcomes, The Flash contends more with reflection and nostalgia. It allows Barry to witness the innocence and joy of his younger self, which underscores a sense of loss that transcends what devastation ensues after his Nora dies. Both films share a central outcome in that Barry ultimately realizes he must undo what he has wrought in attempting to save his mother, as his intervention in the timeline creates a catastrophic ripple effect that throws the multiverse into chaos that leads the alternate realities to the brink of destruction. And while his intentions were rooted in love and grief, he comes to understand that altering the past to prevent an outcome—however tragic—causes more harm than good. The alternate timelines, whether in the form of a world plunged into war in The Flashpoint Paradox or the fractured reality in The Flash, demonstrate the dangers of tampering with time; evincing the consequences of Barry’s actions, forcing him to confront and accept a bitter truth: to restore balance and preserve the greater good, he must return the timeline to its original state, accepting the pain and loss he once sought to avoid. This realization is key in both iterations, reinforcing the [relatively quantum] principle that the past cannot be rewritten without destabilizing the present and future.

In many ways, The Flash personifies a conscious effort to live within the constraints of time, when one realizes that resisting change, tirelessly trying to ‘fix’ things, can be futile. We can recognize that retrograde efforts to ‘fix’ things create more harm than good, so we reconcile what we’ve suffered as we come to terms with the need to move forward. Our misfortunes are fundamental to who, how, and what we become. Which is why the Bruce Wayne in Barry’s original timeline (Ben Affleck) is nonplussed by the prospects of time travel. Quite accurately, he posits that any temporal interference could yield dire outcomes and notes how our adversities shape us. “These scars we have make us who we are,” he says. “We’re not meant to go back and fix them.” We lose out if we fixate on the past in ways that prevent meaningful engagement with the present or future.

For all the disfavour elicited by The Flash—concerning Miller’s exploits offscreen and the studio’s commercial failure—I truly appreciate this film, in that it captures the ethos of the sacred speedster which proves immensely resonant as time goes by. It’s the personal tension between holding onto the past and learning to let go for a greater good beyond oneself, even if it means losing the opportunity to relive a life with neither error nor pain. This alone marks The Flash enterprise as an admirable cinematic feat that explores memory, identity, and the inescapable nature of time. Moreover, The Flash uniquely depicts time travel to evoke an ontological terror that is premised on our own associations with other characters. For example, Michael Keaton reprises his role as Batman; or rather, a Batman from an alternate timeline which conjures nostalgia. Somewhat ironically, as he opines on retrocausality, his presence reinforces the idea that time is fluid and splintered as his familiar likeness is at odds with what we expect. This prompts yet another unnerving realization: any- and everyone, no matter how cherished or iconic, can be altered beyond recognition or repair, by time—which punctuates the chaos that Barry has unleashed. The familiar becomes unfamiliar, which characterizes an existential horror wherein once reliable constructs of identity, memory, and continuity are eroded. As Barry encounters this alternate Keaton-Batman, the film taps into our associations with Keaton’s original 1989 portrayal, but now filtered through the lens of a world that’s doomed and unrecognizable. Time travel doesn’t just threaten cosmic order. It fractures the very essence of the lives, stories, and characters we hold dear.

Which made me think of how Martin Tropp (1990) muses upon what makes for good horror: to “construct a fictional edifice of fear and deconstruct it simultaneously, dissipating terror in the act of creating it” (p. 5). He suggests that horror builds a sense of fear while also providing a way to dismantle or understand it through narrative mechanisms—resolution, confrontation, or explanation—that allow us [the audience] to process and dispel that fear. In The Flash, we see this when Barry sputteringly grapples with the fact that his attempts to change the past bear massive consequences; the terror of unraveling reality itself. And as Barry realizes the futility of his actions and works to restore the timeline, this horror is deconstructed. We, like Barry, come to terms with the inevitability of loss and the cosmic balance, which transforms the initial fear [of losing loved ones and failure] into a shared understanding for the dangers of trying to rewrite history. I can further appreciate this in knowing how the ignoble powers that be, initiate and sustain the historical and ongoing erasure of marginalized positionalities; how the disparities which define us are assured in perpetuity.

Even now, I remember seeing The Flash on the big screen. It was during a time when everything felt hollow, when the anxious pulse of my own vulnerability pressed in on me. Grief over my brother’s death, the ache of feeling expendable, and the dismal horizon of my future—no gainful employment, no promise, no purpose—hung over me. As always, I sought movies as a means to stave off despair. I tried to lose myself in a blur of images, desperate for some reprieve from an endless churn of thoughts and rejections. But I guess I’d grown used to these film reels, so I found myself piqued less by the features themselves than in what mere segments afforded me small mercies; and even those failed to dispel my gnawing sense of negligibility and the loneliness of being unmoored, unseen.

When I was in that theatre, I remember thinking that if I was Barry—stranded in an alternate timeline where heroes who were once widely revered or empowered ceased to exist—I could’ve cared less. Time doesn’t just give context to existence. It agonizes life itself. As a species, we’ve yet to truly evolve or progress. Since history repeats itself in terms of pain, harm, and disparity—regardless of what we do or don’t change—what is the purpose of time, of a life relative to time or other people? While technological and scientific advancements may suggest progress, they don’t address cyclic problems of suffering and injustice. Time is also indifferent to these struggles, as the same issues reappear in new forms across generations. In this respect, time seems pointless, even cruel because it offers the prospect of change without assuring its realization. Therein, time travel becomes a mechanism to explore this horror while simultaneously offering a way to resolve it.

Barry’s journey mirrors the core tenets of horror by confronting not external monsters, but the horrifying reality of devastation caused by his desire to “fix” what was thought to be broken. The fears that premise the time-traveller scenario arise from the catharsis that certain traumas, no matter how painful, are integral to the cosmic order; and that meddling with them can unleash cataclysmic chaos—which aligns with Tropp’s notion that horror works by creating and deconstructing fear in unison. Barry’s time travel offers him a fleeting sense of hope—of reversing loss and rewriting his trauma—but it also creates a terrifying new reality, where his happiness inflicts untold destruction. All iterations of Flashpoint provide audiences with a narrative framework to explore an experience that would otherwise seem chaotic and incomprehensible. In watching Barry wrestle with the horrors of manipulating time, we’re given a likeness to understand our own relationship to the past through a futility of trying to rewrite the inevitable. In the end, this story taps into an existential dread that forces us to confront the immutable nature of time and the consequences of defying it.

And while many people I’ve met have affirmed the existence of fate, that “everything happens for a reason,” it wasn’t until I saw The Flash that I could truly grasp this. Unlike The Flashpoint Paradox, it features Barry’s encounter with a happier version of himself—an alternate self who, in the end, dissolves into the sands of time, embodying the irreversible nature of certain losses. Alternate Barry was just too good to be true. Experiences, no matter how tragic, must remain so for the greater good. The literal and figurative dissolution of Barry’s alternate self speaks to how the personal is more crucial than political. While you may endeavour to change someone or something, unraveling the very fabric of time isn’t exactly selective. Reality and meanings are relative because they coexist. Good is palatable because we discern what is bad. When you aspire to eliminate one, you risk losing both. Just as these opposing meanings maintain balance, the Speed Force governs the equilibrium of time itself in DC Comics. It is an extradimensional energy source that fuels the super-speed abilities of speedsters [imbued with powers like The Flash], enabling them to move, think, and react at lightning-fast speeds, as well as travel through time. Barry channels the Speed Force to become The Flash, using its power to protect the timeline and uphold justice.

On the other hand, Eobard Thawne, the Reverse-Flash, creates and harnesses the Negative Speed Force to maintain his existence and undo The Flash’s heroic legacy. Eobard exists as a living paradox. Despite originating from the future, his existence is contingent upon his enmity with Barry. He continues to exist even when erased from history due to the Negative Speed Force which purposes him outside the normal constraints of time. The lore states that the Negative Speed Force and Eobard’s status as a paradox insulate him from time-altering consequences, allowing him to exist unaffected as timelines shift around him; an advantage Barry lacks. Yet even with this power, Eobard isn’t actually happy. He finds himself at odds, imprisoned in an eternity of obsession despite his freedom from any temporal constraints. He’s denied love, connection, even the very humanity he sought to conquer, illustrating that even mastery over time cannot restore what it takes.

In The Flashpoint Paradox, Eobard appears as the primary antagonist, exploiting the chaos of the alternate timeline to torment Barry and gloat about the catastrophic consequences of Barry’s decision to save Nora. And while he doesn’t appear in The Flash, it was confirmed that Eobard was intended to be the culprit who murdered Nora offscreen. This looms, as his paradoxical existence embodies a cautionary contrast, the very dangers of altering time; a lesson Barry ultimately learns. While Barry seeks to heal past wounds, Eobard thrives on distorting time in an effort to fulfill his own obsession. But this in itself reflects a refusal to change. His attempts to alter reality stem from idealizing or controlling his past, rather than improving who he is in the present. But despite what torment Eobard causes Barry, the latter manages to live a pretty happy life. Although Eobard is free from time, his inability to accept the limits of his own actions resigns him to an endless cycle of misery; a sharp contrast against Barry’s journeys to growth and reconciliation.

I use to identify more with Eobard because of my own pessimistic avoidance, finding his existence as a paradox relatable as a means to shield one against inevitable loss; sparing myself and my beloveds of my very existence and engineering favourable outcomes for us. The Flash allowed me to empathize with Barry as he [his yearning to alter painful events despite knowing the cost] mirrors how I struggle to bear the emotional weight of caring for people who inevitably leave. For me, the film invoked a familiar question: is it worth forming connections that are destined to dissolve, whether through death, distance, or disinterest? The certainty of loss makes every bond feel tenuous, but Barry’s journey imparts that these merry moments may still be worth the pain they bring. The films show us this in a few ways. First, through Nora upon who he warmly scoops into a tearful embrace. Then, in the charmed life of his alternate self. This is also modelled through the multiverse as it begins to implode, conveying that the beauty of connection, however temporary, is intertwined with the certainty of its end.

When alternate Barry dissolved into the sands of time, I bawled. Not because of Miller’s performance, Andy Muschietti’s direction, or even Henry Braham’s cinematography. It was because of the narrative itself. This characterization hinges on the catharsis of one’s own ephemerality. Alternate Barry exists as a flicker against a dying light. He’s a radiant albeit brief impossibility born of a broken time, where his happiness and joy are fleeting in a reality that was never meant to sustain them—which serves as a stark reminder that such sheer happiness can’t persist in a world fundamentally unable to uphold lasting fulfillment. When the sands of time claim him, grain by grain, it marks an erasure of flesh and spirit. Being mortally wounded sees him express a mixture of terror and acceptance, nascent of a child’s dream collapsing into a man’s grief. As he’s swallowed by the very void that his alternative selves tried so desperately to defy, each particle dissolves the laughter that once was. This visualizes the tragic loss of youth and innocence fated to be overtaken by the stark, unrelenting future. His dissolution isn’t just a moment of temporal collapse, but a miserable metaphor for the necessity of growing up and facing harsh realities. To watch him vanish was like watching the erosion of hope and idealism that gives way to the burdens of time and consequence. I felt an unbearable pang as I watched this, like I was witnessing my own innocence being consumed by the relentless hands of fate. Whereas, the Dark Flash, the embittered future [alternate] self—an incarnation of fear and obsession—stands as a testament to the truth I’ve always known but resisted; that happiness, however desperately sought, can’t sustain itself in the shifting landscape of time and loss. There’s an intimacy in alternate Barry’s disintegration that hauntingly echoes my own desire to rewrite past sorrows, yet always knowing that—even if I could go back—the past would remain imbued with the same tragic impermanence.

Initially, I was content to watch to world burn—or in this case, implode—since I was exasperated by the iniquities that vindicate my cynicism. I resolved that if I was Barry, I could’ve cared less [to fix things] because this world’s cons overcome any [highly unlikely] pros and didn’t deserve saving. Like, what’s there to save? The perils of miscellaneous insecurities? The myriad of death and resignation which claimed my beloveds? Prolonging the despair of have-nots against the grain of what profane, performative politics comprise abusers and upper classes? But this scene imparts that time trumps any and every prerogative. It wrenched something raw and vulnerable from deep within, its truth so piercing that it brings tears even now, because it carries the likeness of my own futile longing for a happiness I was never meant to hold.

Charlatans will never see reckoning. Same goes for obscenely privileged positionalities.

My alma mater, amongst other local universities, will never endeavour to retain me regardless of my avowed—and pretty fucking obvious—assets.

My maternal grandmother will never live again.

Neither will my paternal one.

Nor my brother.

Or any other beloveds I’ve outlived.

My family will likely never set aside their petty grievances to simply get along.

My boyfriend’s love will never be totally guaranteed, and he may very well choose to leave me one day although he assures me I’m not expendable [to him].

James and Vera will never be alive again. And as badly as I wish for otherwise, Clark and Edith won’t live forever.

The reality of these impermanent connections only deepens the ache of knowing even the most cherished bonds can never be secured against the passage of time. Yet, time can also proffer great things that endure. I could one day find meaningful, gainful employment where I could work and effect positive change for years to come. My boyfriend has given me some of my happiest moments and our relationship could evolve into a lasting bond in any capacity. And I continue to create meaningful moments with my family in different ways. Even now, I have deeply cherished times with Clark and Edith, whose companionship brings warmth and comfort amid life’s uncertainty. Although I’m mindful of how I can’t be faulted for everything, that certain things are beyond my control, I still feel like I could/should be “accountable” when I fail to ascertain positive outcomes. The Flash motivated me to resist overthinking—via hyperfocusing on particular aspects or points in time—and aspire to be present in the moment, conscious of a grand[er] scheme.

Moreover, time operates on a double-bind of not knowing what’s to come. It’s defined by potential, holding both promise and peril as it unfolds. This uncertainty is equally hopeful as haunting. We know it will bring loss, but we can’t foresee what good may lay ahead. It’s this ambiguity that makes time so daunting yet so full of possibility, as every moment carries the potential to either deepen the wounds of the past or cultivate new, lasting joys. The problem isn’t merely the uncertainty of what’s to come. It’s the question of whether the anguish will be worth it. I don’t exactly fear the adversities time will bring; I just wonder if the bad will ever truly justify the good. Will I see any return on what hope, effort, and love I’ve invested along the way? Can joy, however fleeting, truly outweigh the depths of fated sorrow?

The Flash (2023) seems to suggest the affirmative, as Barry ultimately understands that he must fix what he’s broken in time—not to erase the pain, but to preserve the sanctity that existed in spite of it. His decision reflects that even brief instances of joy or equity can make hardships worthwhile, reinforcing the belief that any good, however small, can transcend the darkness that surrounds it; purposing sorrow as a necessity for the cosmic order. Our despair serves to maintain an equilibrium that governs timelines, peoples, universes beyond our own. The prospect of happier, healthier Fallens who exist elsewhere grants me some closure to make peace with my own indignities; and I’m inclined to count my blessings, appreciating what better living conditions I’ve got in contrast to the Fallens who are worser off.

Likewise, I also understand how disastrous it would be if any of us were to switch places. Imagine if I travelled back in time and wrought a timeline wherein I was a gainfully employed professor, but the absence of my beloveds—and very likely, my conscience—enabled my esteems. Regardless of whether they’d all be alive, I would’ve been estranged from my family. Probably no friends or felines. No boyfriend either. Or, what if my scholarship, salary, and success in that universe were contingent on becoming just as—if not, more—loathsome than the ignobles with whom I currently contend? Even now, I can think of several who are miserable with the familial cards they’ve been dealt. One in particular never misses a chance to impart I’m expendable because I’m not a parent and hold citizenship, absolving themselves of their own complacency, alleging that “suffering” would make me “a better person,” in contrast to more privileged colleagues; while they dote on—sparing no time or expense to ingratiate—themselves amongst internationals and within miscellaneous families in a pathetic effort to vicariously glean some sense of familiarity (notably, parenthood) in lieu of reckoning with their own lack thereof. By their own admission, they’re at odds with relatives—for whatever contrivance or another—wherein immediate relations refuse to indulge or cohabitate with them. It comes as no surprise that they’ve also proven to be anti-Black in imparting likewise, even worse to others. And, there’s another one who opines about how dejected they feel. They resent their family, opting to work late to stall going home for as long as possible. Their significant other functions less as a partner than a ward alongside the progeny neither can seem to civilize, whose narcissism grows as they do and renders their antics more of a nuisance than “cute.” Then, there’s the nepo-hipster whose parents’ [formerly tenured professors] spoils inclined them to cosplay as a queer liberal to supplant an utter lack of self-awareness.

I could go on, but I digress. At the core, this intricate weaving of timelines and alternate selves echoes The Flash’s emphasis on why tampering with time, no matter how well-intended, can yield unforeseen horrors. As Barry confronts the potential cost of rewriting his past, I too recognize that achieving certain desires could mean sacrificing what makes my life meaningful, even if imperfect. In addition to many others, the aforementioned ignobles deplore accountability as much as honesty and kinship, even as they claim—and build personae based on—the contrary. Their measly modus outdoes any vocational and financial fulfillment to the extent that their vanity and trivial pursuits betray them being hollow, condemned to dissatisfaction. Which prompts me to be mindful of the moment. The Flash accentuates this, showing that the real tragedy lies not in what is lost, but in what could be lost by pursuing an illusion of “better.” Some things are truly too good to be true.

Some times too.

♫ Title song reference – “For the Good Times” by Al Green