Around the time I got Clark, I was binging Smallville. I thought that his muscular build likened him to ‘The Man of Steel.’ He was the fittest, largest cat I’d ever met, weighing in at 22 pounds at his heaviest; but he never had any health issues and was always active. I think that I only really started to process change or “expect the unexpected” after I got Clark. I never actually planned on getting him. Initially, I got James. Edith came along after my mom’s former boss offered her years later. Then, I got Vera to be Edith’s friend since the age gap between Edith and James meant they weren’t too friendly with each other. They got along, but James was older and exasperated. Clark was the anomaly: a mouser meant for the rural living space I shared with my father. I’d hoped to bring James or one of the girls there, but my mother forbade it. Being a woman of action, I just resolved to get yet another cat.

Clark and his siblings were advertised in local classifieds although there were no pictures; but back then, just the word “kitten” was enough to generate interest, and pickup was well within range of my daily commute. So, I set out that frosty morning after a quick phone call [to the classifieds poster], then thrifted a sturdy cat carrier before I made my way over. Given the genders as they were—the pair of girls and James—I figured it’d be ideal to even things out with another boy. Clark was the only guy left when I got there. He was also the only shorthair—or short-ish, given how it would grow to be relatively wavy and mid-length—unlike his sisters. I don’t know if Clark was the runt of his litter, but he’s acted as much since as the youngest of the others. Even more memorable was how neither he nor his sisters were separated from their mother, which is usually advised since cats can be protective of their kittens if someone attempts to take one; but Clark was the only one unnerved when I took him. I’ll never forget the indifference of his mother and sisters, even his father who lounged on the backyard patio.

Clark was meowing a lot despite my assurances. I chalked this up to nerves, not unlike the others I had when I first got them; but time would reveal Clark to be chatty, now sassy. I also suspect he was hard of hearing due to how loud he’s always spoken. Anyway, Clark was roughly two when we came to live with the others after my father moved. While they eventually tolerated him to varying degrees, his later introduction marked him as an outlier. I used to feel bad because I often wondered if he felt lonely or ostracized, and I guess I projected some of my own feelings of that onto him since I knew how that felt. I knew what it was like to be bullied, so I learned relatively early on how people could be tirelessly cruel and relentless; how it felt trying to belong only for prevalent disparities to render all efforts fruitless; having every amity or crush be rendered likewise, yet still vying for reciprocity. Essentially, Clark personified what alienation defined—and honestly, continues to rationalize—my social anxiety and aversion; but as a caregiver, this was something to behold. Seeing how Clark was typically excluded by James and the girls, I always made a conscious effort to dote on him; but I knew for however earnest my efforts were, I was no substitute for acceptance at large.

What I didn’t know was that my efforts weren’t for nothing. It never occurred to me that Clark notices, cherishes, and loves me because of them. For years, I assumed he was aloof and miserable. I worried that it wasn’t enough to just care; that I could never fill the void left by his exclusion from the others, that he must feel as lonely as I usually do. But recently, I’ve come to realize that Clark’s love has always been there—shrewd, steady, and uniquely his. It’s in the way he seeks me out, even when he could easily retreat to his favourite hiding spots; and how he lingers near, brushing against me or calling. Then, there’s how he bunts me. He didn’t need validation from others. Instead, he was simply content to exist with me. I used to think I was trying to fill a gap in his life, to compensate for something he lacked. Now, I understand that Clark has been filling a gap in mine. He’s shown me that love doesn’t have to be loud to be real and that even the smallest efforts to care for someone can create a bond that speaks louder than words ever could. Clark had also been a steady and surprising source of comfort throughout Edith’s terminal diagnosis, showing me another side of himself I never noticed before. He seemed to sense my sadness, appearing by my side just when I felt most overwhelmed, letting me hold him and holding me. His calls, once simply part of his quirky personality, had become a call to action that motivated me to get up, keep going, and stay present for the both of them. In these moments, I saw a more intuitive side to Clark, one that reassured me I’m not alone.

Which is why I found myself reconsidering his namesake. Likening him to Superman, I’d mostly thought of strength, endurance, and physicality. After Smallville wound down and I rewatched the animated series, I saw how the name also meant resolve and loyalty. Superman was never just a symbol of might. He was an outsider who navigated loneliness while carrying an immense capacity for love. He also realizes that fulfillment isn’t found in grand heroics or cosmic purpose, but in the quiet, simple moments; the small joys of an ordinary life, and understanding that being human, in all its imperfections, is enough. Every trial and tribulation drives home the importance of those who see him as more than Superman.

In many ways, Clark has shown me the same. All my overthinking, overdoing only to realize that nothing is ever enough; that systems are incorrigible in what and who they oblige. I used to think getting to the bottom of the how and why would help me make sense of the what and render the when and who more discernible—but that was never the case. People are too fickle. Their ignobility is on par with their ingenuity to conjure sentiments and scenarios in which little, if anything gets addressed lest we fail to accommodate endless variables. Complicating life just makes us lose sight of what truly matters: the pure, unspoken bonds that don’t need justification or grandeur to be meaningful. But while simplicity reveals what truly matters, too many mistake submission for security, believing that aligning with power will shield them from its corruption. Superman also understands that no amount of strength can truly dismantle the iniquity that defines this world, but he still chooses to exist within it and strives to do good however he can. Clark taught me that even in a world where I can’t change the larger forces at play, the simple act of caring, being present, and finding comfort in moments still matters. Maybe Superman’s greatest act isn’t saving the world, but finding peace in knowing even small acts of kindness are worth something.

And as I consider this, I can’t help thinking of Saw 4 and its ill-fated protagonist, Daniel Rigg (Lyriq Bent), who was ultimately destroyed because his defining trait—his inability to let go—was manipulated against him. While imperfect, his compassion and drive to save others was genuine; but instead of being given the space to learn or change, he was forced into a test designed to ensure his failure. Saw 4—specifically, how much I’ve always despised how it ended—showed me how much I fixate on inconsistencies, injustices, and unresolved truths because I refuse to compartmentalize or dismiss what feels fundamentally wrong. Rigg’s trial reflects the cruel irony of a system that punishes those who care too much and twists virtue into weakness, exploiting it rather than guiding it toward growth. In the end, Rigg didn’t fail himself; the game was rigged against him from the start.

Kinda like the last son of Krypton. For all his strength and idealism, Superman is ultimately doomed to fail because his unwavering sense of duty and a need to protect everyone—the very qualities that make him heroic—are also the ones that leave him burdened, isolated, and vulnerable to being twisted by grief, disillusionment, and the impossibility of saving a world that refuses to save itself. There’s a tension between what he needs to accept and what he feels responsible for. No matter how much he tries to let go, knowing he could do more gnaws at him.

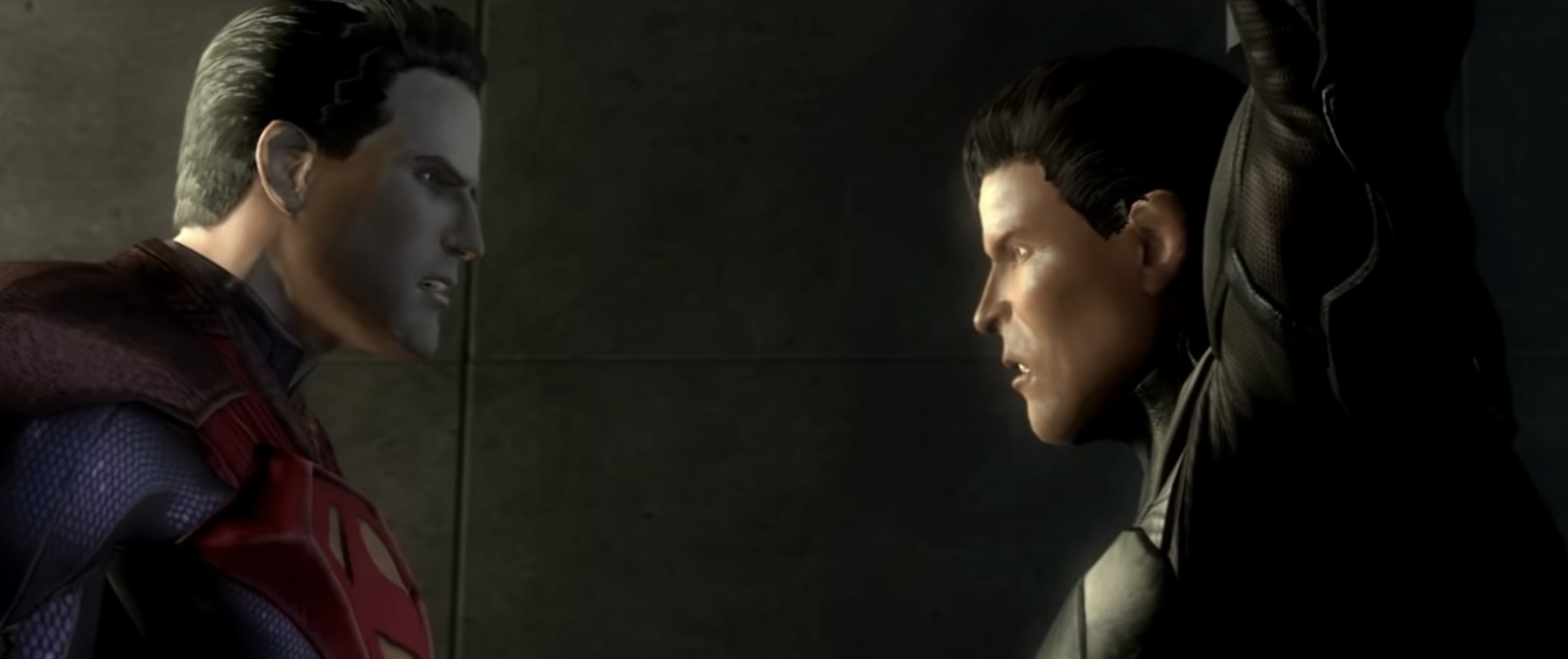

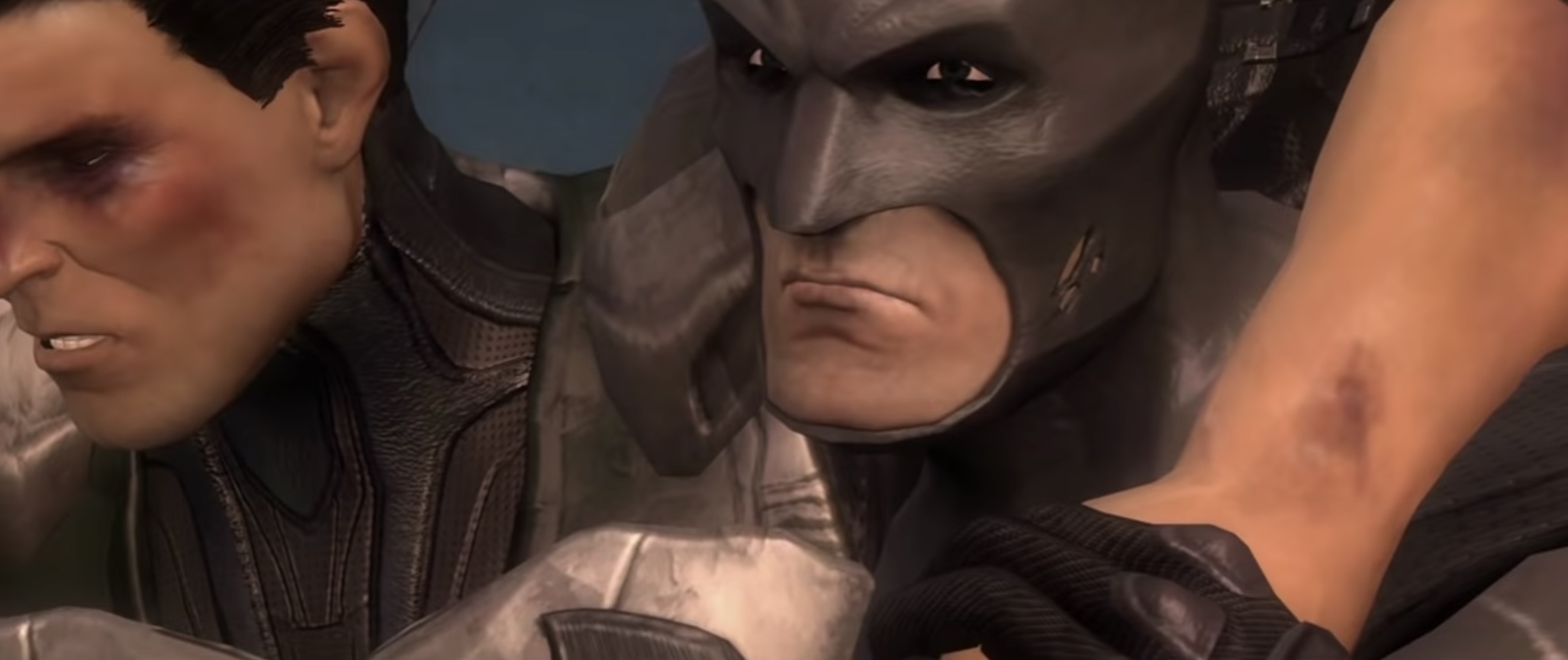

At its heart, Injustice: Gods Among Us (2013) depicts Superman’s inability to let go and accept that some battles can’t be won. Not everyone can or should be saved. Unlike many DC storylines that originate in print and later expand into other media, Injustice was made specifically as a game narrative, integrating complex character drama with the mechanics of a fighting game. Adding to its impact, the game features most of the iconic voice actors from Justice League and other beloved DC animated projects, which lends a sense of familiarity to a story that takes these characters into uncharted territory. Set in an alternate DC universe, the story casts Superman (George Newbern) as a tyrant after the Joker (Richard Epcar) tricks him into killing Lois Lane and their unborn child, which also detonates a nuclear bomb in Metropolis. After killing the Joker in rage, he establishes the One Earth Regime, a totalitarian government that enforces global peace through absolute control. Most heroes—including Wonder Woman (Susan Eisenberg), Green Lantern (Adam Baldwin), Aquaman (Phil LaMarr), Cyborg (Khary Payton), Shazam (Joey Naber), and The Flash (Neal McDonough)—join him alongside villains. Resisting Superman’s rule, Batman (Kevin Conroy) forms the Insurgency and allies himself with Lex Luthor (Mark Rolston). He transports alternate versions of himself, Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Aquaman, and Green Arrow (Alan Tudyk) from our universe. With their help, the Insurgency fights back, leading to a climactic battle between the two Supermen. Our Superman defeats the tyrannical one, and Batman imprisons him in a red sun cell, ending his reign—for the time being.

Superman has always understood death as an inevitable part of life. He was sent to Earth because Krypton perished. Then, he was raised by Jonathan and Martha Kent whose values shape his dealings with loss as both Clark Kent and Superman. They taught him humility, responsibility, and the limits of power. Logically, Superman knows that even with all his strength, he can’t stop death from claiming those he loves. But Injustice exposes a contradiction within the Man of Steel: while he accepts death in theory, it is also his breaking point in practice. The loss of Lois and his unborn child doesn’t just devastate him; it shatters the core beliefs that have always tethered him to restraint. Instead of seeing death as a painful but natural part of existence, he sees it as a failure to protect what matters most. And from that moment on, he refused to ever let it happen again, no matter the cost. Long interpreted as a Christ-like figure: Superman is an all-powerful being sent from above to guide and protect humanity, sacrificing himself time and again for the greater good. In Injustice, that messianic role warps into something authoritarian. Instead of offering salvation through faith, hope, and inspiration, he demands it through force and obedience. He no longer trusts people to follow the right path; he compels them to. In that sense, this Superman shifts to something more akin to an Old Testament deity or even a fallen angel. Injustice casts him as an absolutist where any threat to peace must be eliminated by force, if necessary. He believes he’s doing what’s best for humanity; but in doing so, he strips people of their freedom and autonomy, enforcing his will rather than allowing people to make their own choices. He becomes the very thing he once fought against: a tyrant no different from Darkseid or Lex Luthor; wielding power not as a protector, but as a ruler who demands submission in the name of his own vision.

A happier read would say that Injustice Superman is righteous albeit misguided as his need to save people morphs into a compulsion that blinds him to reality, that he truly believes he’s doing the right thing; although in the end, his inability to let go causes more harm than good and leads to his own demise and those of others. Superman cares so much that he refuses to accept some people don’t want to be saved, or that trying to help can make things worse.

My pessimistic read—and perhaps, a more honest one—suggests that Superman’s downfall isn’t just a tragic miscalculation, but an inevitability. His belief in doing the right thing was only righteous when it aligned with the ideals he once upheld. The moment the world deviated from his vision, he abandoned those ideals in favour of control. His need to save people was never truly about them, it was about his own inability to tolerate loss; and his refusal to accept that suffering, injustice, and even death are woven into existence itself. And in his desperation to rewrite the rules of reality, he proves that power—no matter how noble its origins—can corrupt. Not because it changes those who wield it, but because it reveals what was always there: the capacity to enforce, to dominate, to reshape the world in one’s own image, no matter what or who must be sacrificed along the way. Even now, I can’t help but recall the people I’ve encountered who gained more systemic power. I think of the long-term commitments I’ve made, the communities and relationships that once gave me a sense of belonging—only to be met with the realization that they never truly saw me as part of them. Everything just vindicated my misanthropy or distrust. This kind of disillusionment runs deep, especially when it comes from people or institutions that proffer justice or belonging. It’s one thing to see power corrupt from a distance, but another entirely to witness it in those who position themselves as advocates or allies. When people who preach about accessibility, equity, and inclusion turn out to be just as self-serving and complicit as those they claim to oppose, it only reinforces the sense that power—no matter how it’s framed—always bends toward self-interest. And worse, when you’ve worked so hard, given everything just to be part of something—only to be told you’re not enough or that you don’t belong, it makes the very concept of community feel hollow. Sure, nothing in life is guaranteed. Loyalty shifts, promises break, and most beliefs change over time. But what’s constant is the consolidation of power. No matter the era, ideology, or individuals involved—power gravitates toward itself, building in the hands of those who hoard it, at the expense of those who don’t. Systems and seasons may change, but the outcome is always the same. Those with power find ways to keep it, and those without perish. They’re in favour of anything, anyone that consolidates power into their hands; and they’re against the (re)distribution of power—social, monetary, or otherwise.

Fundamentally, it’s conservatism; they’re just content to conserve the status quo so long as they reap its benefits. Norms inform their complacency because that’s “just the way it is.” The way it is premises what should be. This is how power is sustained. This is also how—and why—conservatism is readily co-opted by fascism, the latter of which assumes a hierarchy that admonishes minorities. While conservatism alleges democracy assures [its] fairness, fascism dismantles its foundational principles to accumulate more power. Terms like “SJW,” “woke,” and “virtue signaling” define many of their insults because they believe in innate differences. They can’t believe any sincere calls for equality, only that these—and any—efforts are just ways to take power; ways that they themselves would also exploit. This also explains why conservatives readily accept charity but resist systemic change; they view charity as goodwill from those who’ve “earned” their status, rather than as something those in need are entitled to. In their view, assistance should be an act of generosity, not a right.

Even in light of current events, I don’t believe we’re experiencing a conservative or fascist shift in politics. I think there is a social incentive to embrace conservative politics that can translate into financial incentive, but it’s not the same. Folks tend to frame things as a progression of conservative and fascist influence, particularly because that fits a very profitable narrative for conservatives and liberals who monetize the ensuing miasma of despair. I do believe that billionaires and ownership classes embrace fascism as a means of self-preservation; and their fans carry water for oligarchs and deplorables. Bearing this in mind, it’s no surprise that celebrities, politicians, and the corporate class are openly investing in conservative politics. My point here is that power is subtle. Comparably, desperation is overt. True feelings are closer to the heart rather than the mouth, and we’d all do better to listen to the pulse being drowned out by the chatter. Pretenses ignore the root causes of desperation, offering empty gestures instead of meaningful solutions, leaving the most vulnerable with no recourse but to fight for what they were never given. Violence ensues from performative—as opposed to anti-oppressive—politics because dehumanization begets it. This relates to the paradox of righteous indignation which starts as a response to injustice, yet consumes the very virtues it aims to uphold in seeking to correct the world’s wrongs.

This underscores the rationale of Injustice Superman and likewise powers that be. Power isn’t about morality, justice, or fairness; it’s about control. Those who hold power justify their grasp through brute force, social conditioning, or the illusion of goodwill. Injustice Superman believes that he alone has the strength to shape the world, so he alone has the right to dictate its future; much like how the ruling class rationalizes their dominance under the guise of meritocracy, tradition, or “the natural order.” So, power is not something to be shared, only wielded. Any challenge to their authority is framed as an existential threat. Not because it disrupts peace or stability, but because it disrupts their place at the top. Those in power would rather concede charity than equality, and grant favours rather than dismantle the structures that necessitate them. The consolidation of power is the only true constant, and those who have it will do whatever it takes to ensure they never lose it. Injustice Superman succumbs to the idea that power alone justifies action. He concludes that because he can impose his will, he must. His strength warps into entitlement to which his vision of peace becomes tyranny. The more power he amasses, the more tortured he becomes. As external resistance mounts, his own convictions demand endless escalation. His pursuit of order doesn’t bring him peace; it only deepens his suffering. No amount of control can undo the grief and regret that set him on this path in the first place.

Sometimes, I genuinely miss being radically hopeful with the belief that all people are inherently good, and corruption stems from greed and power rather than something more fundamental. I miss the good feelings that came with that faith in humanity. I miss not being consumed by anger and fear. I long for the time when real, mortal danger felt distant enough to moralize over. I miss feeling safe and valued, and believing safety and value were things I was inherently entitled to. I miss not being so [rightfully] pessimistic. Now, I’m mad, bitter, and resentful because it all proved to be a fucking lie. Unlike Injustice, there was never any Insurgency in real time. Having spent my life working toward a professorship—fast-tracking my degrees, sacrificing stability, and striving for academic excellence—I’ve seen firsthand how tenure operates as a gatekeeper of power in academia, determining who gets security, influence, and a voice, while those without it remain precarious, expendable, and unheard. Tenure is a permanent academic appointment that grants professors protection from dismissal, giving them the freedom to research, teach, and speak without fear of institutional retaliation.

However, it also consolidates power, creating a hierarchy where tenured faculty have significant influence over hiring, policy, and academic discourse, often reinforcing existing inequalities within the university system. It’s depressing that precariously employed faculty and students—some who haven’t even finished their degrees—risk everything while tenured professors stay silent, unwilling to even read a statement condemning injustice on campus. People rush to name a few exceptions, but the reality is that most faculty uphold the very systems they critique in their writing. For them, there’s no praxis—just lip service and theory because, at the end of the day, it’s a career. They talk about “decolonizing the university,” but decolonization isn’t found in edited collections or overpriced conferences; it’s a material struggle. Soon enough, we’ll see “radical” faculty publishing books and articles on student activism, but don’t expect them to stand with actual student protesters or part-time colleagues. Universities will house specialty centres where tenured “progressive” professors lecture about revolution—while their students and part-timers are sanctioned for resisting oppression or abusive faculty.

As this present feels like a betrayal, it’s easy to retreat into the past, searching for a time that felt safer, more certain. Nostalgia lulls us into the illusion that the past was a sanctuary, a place where love was certain, where we were whole. I miss the past, when my beloveds were alive and their presence felt certain, when I could still believe that love and companionship were constant rather than fleeting. Back then, I had the comfort of assurance in knowing they were there, that they existed in the same world as me, that I wasn’t so alone. Now, I am bereaved, hollowed out by absence, and eclipsed by forces beyond my control. Mortality reveals itself with ruthless clarity; and worse still, I can’t stop those I love from leaving me—by fate or choice. I agonize over whether the people I love truly love me enough to stay, or if they merely tolerate me until they no longer can. I wonder if I’m nothing more than an expendable nuisance as I’ve been so easily discarded. Uncertainty gnaws at me, whispering that I’m always one misstep away from being abandoned, one inconvenience away from being left behind. I know I’m operating from a place of trauma, but also from an unrelenting nihilism that seeps from my pores—and I hate it. I don’t know how much longer I can productively sublimate it, or if I’ll know what to do when I can’t.

I don’t know how to accept being powerless.

History imparts that most people are only a nudge away from engaging in harm or cruelty when provided with the right justification. Social structures, ideological conditioning, and collective narratives offer the necessary pretext for moral disengagement, enabling individuals to commit or condone harm under the guise of righteousness. As Aldous Huxley observes, one of the most effective ways to mobilize people toward a so-called noble cause is to grant them permission to inflict harm upon others. This reinforces the cruelty of righteous indignation, the pleasure gleaned from harm when framed as virtuous or necessary. Similarly, Friedrich Nietzsche notes that every society harbours people who derive great satisfaction from acts of violence, particularly when those actions are framed as retribution. Huxley extends this idea further by arguing that such moral crusaders rarely operate alone; and that they easily recruit others into their cause because righteous indignation carries an undercurrent of noble sadism, a latent desire for domination that only needs minimal provocation to manifest. This phenomenon is frequently exploited by those in positions of power, who manipulate public sentiment by rebranding systemic harm as an unfortunate but necessary step toward a greater good. Harmful policies, punitive social norms, and exclusionary ideologies are then justified as regrettable yet unavoidable measures required to maintain order or achieve an idealized future. Thereafter, Huxley concludes that the ability to enact iniquity in good conscience is a heady treat, and those who relish this power don’t actually seek justice or progress.

They seek pleasure by inflicting punishment. Recognizing this—seeing the cruelty of righteous indignation for what it is—is crucial to call bullshit on performative movements, ideologies, and institutional rhetoric that claim to be driven by moral imperatives while enacting policies or practices that perpetuate violence and oppression. In addition to cruelty, Injustice Superman demonstrates the folly of righteous indignation altogether. He purposes his bereavement as a personal call to action rather than an expression of underlying tensions which peak due to a tragic stimulus. Hence his exceptionalism inspires tyranny and prevents him from seeing the mechanics of his own downfall therein. Injustice sees Superman exhibit a hubris of sanctimony that leads to subterfuge and failure—but hubris has always been intrinsic to Superman, right? After all, shy of kryptonite, his power fosters a belief in his own glorious purpose. Arguably, this makes him susceptible to the illusion that he alone can oversee order and justice. I also can’t help thinking how, systemically, hubris is a curious thing.

When individuals repeatedly succeed within systems designed to favour their advantages—wealth, extroversion, timing—they tend to believe their privileges substantiate their greatness. Cultural narratives around genius, exceptionalism, and inimitability reinforce this illusion. Psychologists termed this to be the hot hand fallacy, an illusion gleaned from a pattern of success. Essentially, the illusory belief [bias] that past success increases the likelihood of continued success, rather than recognizing it as a probabilistic [systemic] outcome. This bias is bolstered by our cultures of individualism where outcomes are [often erroneously] attributed to personal agency over systemic or situational influences. Injustice Superman’s brand of hubris—his belief that he alone is responsible for order and that only he can save humanity—fits within this broader cultural mythology. However, his power is not merely the result of his own strength or will, but rather an outcome of systems reinforcing his position. So, he fails to realize how contingent his power truly is. His downfall doesn’t come from a single misstep. It comes from the very same systemic forces that once empowered him, now shifting against him. Moreover, Injustice Superman’s downfall can be understood through a drift into failure in how the slightest deviations from ethical decision-making gradually become normalized, leading to disastrous consequences.

Humanities researcher Sydney Dekker speaks to this, noting how behaviours that are initially seen as justified or even beneficial can reinforce a false sense of security over time, which makes it difficult to recognize when success has turned into failure. Local rationality can put this in perspective too. Philosopher Karl Popper terms this to abstract the principle that people do their best with the cards they’re dealt. It’s commonly referenced in the context of failure for workplaces and high stakes scenarios. It’s purposed to put the mechanism of failures in perspective. Ideally, localizing and identifying variables that factor into failure would prevent another; but this somewhat absolves personal accountability despite acknowledging that we’re resigned to our constraints. It’s not that we should be, do, aspire for better; it’s that folks should recognize—and appreciate—how much it takes just for us to get by. The world is shitty as is. So is life as we know it. We see injustice firsthand in fuckface billionaires, grifters, and charlatans. Given the state of the world, just getting out of bed entitles us to something—and yet, we still end up coming up short. If anything, it’d be “rational” to burn everything down. I don’t say this out of nihilism and misanthropy. I say this knowing that the powers that be are only concerned with identifying or localizing variables not to prevent failure, but to assure their own success. They seek to sustain a supremacy premised on history. Because his decisions consistently yield positive results in the past, Injustice Superman is convinced of his superiority. Every success strengthens his belief that he alone can succeed where others would fail, fostering a hubris that blinds him to the growing dangers of his authoritarianism. Since his system continues to function—sustained through fear and control—he can’t recognize its flaws and instead doubles down on his every action; and the drift of failure peaks when an individual believes they’ve secured absolute control. Which is why Injustice Superman, never hesitates to eliminate perceived threats and surrounds himself with voices, villainous and otherwise, that validate his authority. He purges opposition, centralizes power, and positions himself as the sole arbiter of order to create a pretext of dominance. Still, this sense of certainty dooms him to fail because it occludes a fundamental truth: control, once total, becomes inflexible—and what can’t bend will break.

This reflects the paradox of power: its greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. At its peak, authority is most fragile, because it thrives on reinforcement rather than adaptation. It minimizes dissent but also eliminates the very structures that allow for course correction. Injustice Superman, convinced of his own invincibility, fails to see his tyranny makes his rule brittle. Despite his belief in total control, Injustice Superman’s authority remains dependent on external forces—political structures, technological infrastructures, public perception, and the compliance of those beneath him—all of which he has steadily eroded. In trying to secure his rule, he unknowingly pushes his system to its breaking point, amplifying complexity and fragility. Each new decree, purge, or restriction entangles him further in a web of dependencies, where every effort to tighten his grip introduces new vulnerabilities.

This growing web of power and consequence creates a reality that nobody can fully comprehend, let alone control. Injustice Superman, having designed his immediate surroundings to suppress dissent and eliminate corrective feedback, believes himself to be more in control than ever, even as the foundations of his authority begin to erode. Each purge, each reactionary decree, further destabilizes the system he seeks to command, creating unforeseen and uncontrollable ripple effects. At this point, his downfall is no longer a matter of if, but when and how—not the collapse of a man, but of a regime that could no longer sustain the weight of its own contradictions. What he perceives as consolidation is, in reality, the acceleration of his own collapse. He reacts with increasing volatility and paranoia leads him to lash out. He sees betrayal at the slightest hesitation and insolence where there’s doubt. And, he infantilizes us [humanity] as “disobedient children” who “must be punished.” Each decision and rationale grow more reckless, fuelled by the false confidence that past successes ensure future triumphs. His hubris becomes his undoing and resigns him to an uncompromising cycle that leaves no room for adjustment or retreat, augmenting the structural dimension of One World Regime’s collapse. Systems built on fear can only hold as long as their subjects do not resist. Over time, the Insurgency and humanity itself reaches a breaking point. When the illusion of Injustice Superman’s invincibility fractures, the Regime crumbles. His cruelty and paranoia are consequences of his own design, not mere symptoms of fear. The more he seeks to suppress “disorder,” the more isolated and precarious his “order” becomes. This ensures that when his fall comes, it will be as inevitable as it is absolute.

Again, this defeat doesn’t occur as a singular moment, but as an inevitable consequence of a power that can no longer sustain itself. Which makes me wonder if power can exist as something deeply personal, tied to love and connection. I can’t think of any instances of integrity that weren’t shaped by the influence of power. Power is a construct of those who wield control. Integrity, in the way it’s commonly defined, is always shaped by larger power structures, but the kind of power that exists in love—such as the love of beloveds like Clark—is something different. It’s not about dominance, control, or historical narratives; it’s about care, memory, and the quiet influence that lingers even after someone is gone. Maybe that’s a kind of integrity, or at least a form of goodness that exists outside of the systems we usually associate with power. Love, in its purest form, doesn’t need validation from authority or history—it just is, meaningful in ways that don’t require justification. However, in a world where injustice prevails, even something as pure as love doesn’t exist in isolation. Love is shaped by the very systems that seek to undermine it, making it both a refuge and a liability.

Given the prevalence of iniquity, love is an externality we create which comes back to destroy us. Love isn’t just something we experience. It’s something we bring into existence, something we shape and invest in—only for it to turn against us through loss, betrayal, or the inevitability of time. In a world defined by injustice, love becomes an attachment that exposes us to pain rather than protect us from it. When everything is fleeting, when even the strongest bonds are ultimately broken, love feels less like a refuge and more like a prelude to devastation. Yet, despite this, love still holds meaning, and though its impermanence feels more like a burden than a gift, I remain grateful for it. It feels almost unreal that I have Clark. He brings me a love, care, and support so profound that it sustains my belief in good. In a world so unkind, Clark reminds me that some things—some bonds—are real and worth holding onto. I don’t know if I’ll ever see Superman flying overhead, but I know love is the one thing that will lift my gaze toward eternity.

What marks Clark from his Injustice namesake is that he doesn’t let power corrupt him. Cats have an evolutionary intelligence. They meow to mimic human baby cries, an adaptation designed to elicit care and attention. It’s an effective tactic to ensure their needs are met. And yet, Clark, for all his intelligence, doesn’t use this ability to manipulate or control. He has the ability to influence, but he doesn’t seek control. He can easily summon me with a call, demand my attention and know I’d give it. Arguably, he could also call me endlessly and solicit more than he needs, but he never does. He remains steadfast as he ever was, clear of the hunger for control that fells even the greatest of humans. If only the same could be said for those who have known the taste of power and, finding it sweet, could never again be sated. He’s also powerful in his own right—muscular, large, capable—but remains darling nonetheless. His strength doesn’t demand submission; it invites affection. He doesn’t use his might to take control, nor does he feel the need to dominate.

In Clark, I see an alternate path to power—one that does not seek to rule or reshape the world, but simply to be, content in existence rather than in control. Which brings to mind a quote from our Superman after he bests his tyrannical alternate in Injustice. “Put in the same position, I might have done the same thing,” he admits, “We never know what we’re truly capable of.” This acknowledges that morality isn’t fixed. Under the right—or wrong—circumstances, even the best of us can become something unrecognizable. It’s easy to condemn Injustice Superman and see his descent into tyranny as a choice that only he could make; but the good Superman’s admission suggests that his fall wasn’t an anomaly, but a possibility that exists within anyone, given the right pressures, losses, or justifications. Which ties back to the way power consolidates, the way people rationalize holding onto it. Injustice Superman never intended to become a dictator. The scariest part isn’t that he fell; it’s that, under similar conditions, we all could.

However, Clark stands as a counterpoint to everything Injustice Superman represents. Where the eponym sees power as something to wield, the namesake simply exists in it. While Clark’s nature may be uniquely his, the love and care I’ve given him have surely shaped that. Even if he was always inclined to be gentle and secure in himself, I’ve reinforced that he doesn’t need to fight for attention, control, or validation. Maybe he knows he’s loved, and that certainty frees him from the impulses that drive others to grasp for power? If Injustice Superman’s downfall was always a possibility given the right pressures, then does the same logic apply to Clark in reverse? Could it be that, no matter the circumstances, he simply wouldn’t seek control because it’s not in his nature? Or is his contentment, his quiet resistance to power’s lure, a reflection of the environment I’ve fostered for him—one where love is given freely, where he has never needed to fight to be seen? It makes me wonder—if Injustice Superman had been reassured of love and security rather than losing them so violently, would he have been able to resist his own worst impulses? Or was his fall inevitable the moment he realized that, despite all his power, he couldn’t control everything?

To me, it’s not about wanting power or control. It’s about recognizing that no matter what is done, people will always find something to criticize or tear down. Injustice Superman, for all his strength and conviction, sought to impose order on something inherently chaotic: human nature. But even if he’d succeeded, would it have mattered? Would people have truly changed, or would they have simply resented him until they found another way to tear it all down? Which kinda acknowledges what Superman never could—some things simply are, no matter how much effort is poured into changing them. That’s why Clark, in his simplicity, feels like such a contrast. He doesn’t try to change the world, he’s just in it. That’s a kind of wisdom Superman never had. Regardless of everything else—disillusionment, exhaustion, the flaws of the world—I still hold onto love, and I still give it freely. Clark may not express it in words, but in his way, I believe he knows I love him too. He reflects that love back in his bunts, purrs, presence by my side.

And the fact that I continue to pay it forward, even with everything I’ve been through, speaks to the depth of my own heart. Honestly, I think that, despite everything, love—Clark’s, mine, in general—still holds meaning, even if the world itself doesn’t seem to reward it. Even when it isn’t reciprocated or rewarded, love still carries weight. Injustice Superman’s love for Lois and the world was real, but he let his regret twist it into something transactional wherein love only had meaning if it was preserved, protected, and controlled. When the world failed to uphold his love, he abandoned its mercy and turned it into justification for domination. But Clark’s love exists simply because it is, not because it must be proven, enforced, or rewarded. That’s the real tragedy of Injustice Superman—not just that he fell, but that he stopped believing love had value outside of his ability to safeguard it.

For as lost as I feel in life, Clark isn’t lost with me. I’m his home. I don’t feel like I’m doing enough, but Clark’s love is proof that I am. Even when I’m anxious about the future, Clark is still here in the present, purring beside me, choosing me. And in that, there is love. There is certainty.

There is enough.

♫ Title song reference – “I’d Love to Change the World” by The Zombies